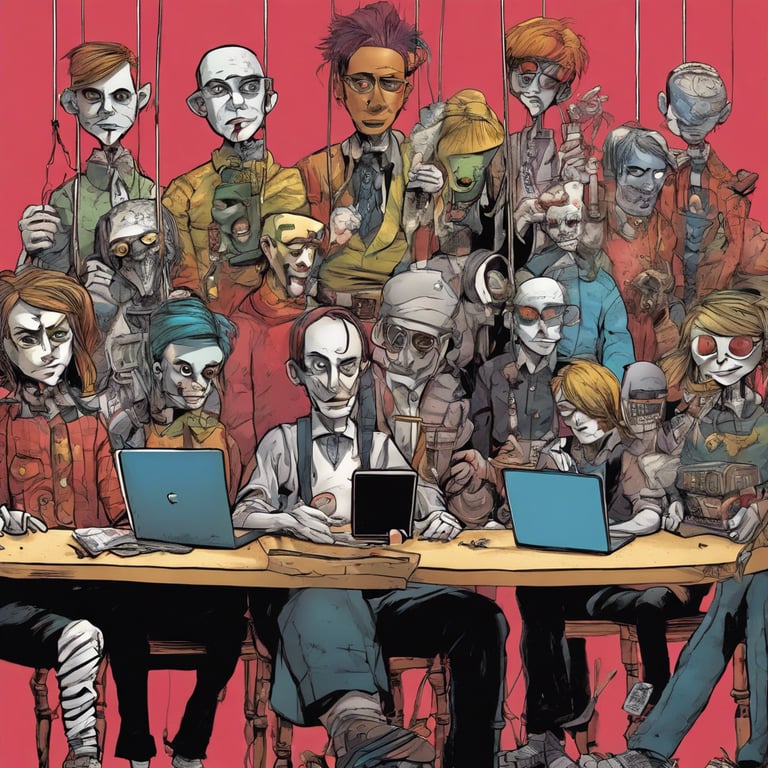

The machine doesn't stop: The health implications of social media

Is social media good or bad for our health? With so much conflicting information, it is difficult to get to the bottom of it. Here, I unpick the tangled strings to consider its net implications on wellness and quality of life.

SOCIAL WELLNESS

12/2/2023

'"How we have advanced, thanks to the Machine!” said Vashti...“Cover the window, please. These mountains give me no ideas."'

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, 1909

Fair warning, this is a fairly big one! It's a huge topic with lots to cover (and I kinda got on a roll!), so here's a menu to navigate if you want to jump around.

Today, I turned to my website builder to write this following a dive into the scientific literature on the topic, rolling up my sleeves to craft a message as a translation of my research for those interested in reading it.

I navigated to the appropriate menu area and hit 'add new post'. Confused by the instructions in the box that popped up, I exited out and hit the button again, thinking I had accidentally activated the wrong prompt. I repeated this process a couple of times and finally assumed that the builder tool had changed the process for writing blogs. Then, a very fine print link at the bottom of the dialogue box caught my eye. It read: 'Skip, I'll write it myself'.

This link sat at the bottom of a number of input fields through which I could instruct AI to produce my blog post on my behalf.

Am I just resisting an inevitable shift in business practices by incredulously thinking that NOT writing your own article as a representation of yourself and your business brand should be the afterthought, not the other way around?

In this moment, I can see that we may have reached the other side. Have we, en masse as a homogenous collective at least, settled on the fact that we now 'consume content' without considering or caring about where, or whom, it comes from?

The irony is that the topic of this post centres upon my concern about the health and quality of life risks of social media design and subsequent use - a closely related topic where creating and consuming digital content is concerned. It only solidifies my deep worry, and it is from this place that I put virtual pen to paper.

'“You talk as if a god had made the Machine,” cried the other. “I believe that you pray to it when you are unhappy. Men made it, do not forget that. Great men, but men. The Machine is much, but it is not everything."'

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, 1909

Living in a digital world, but I am not a digital girl...

The Wellness Unplugged initiative

Learn about the initiative that I am currently nurturing as a response to the topic of this article

It may seem strange to see a Nutritionist write about a digital tool. What does this have to do with food? Well, other than the fact that many people rely on social media for health and nutrition guidance (1), my interest in the topic is multifold. My qualifications include psychology, sociology and public health promotion, and have thus firmly planted my interest in how our day-to-day practices affect our overall state of wellness. As a Nutritionist, I practise holistically because I understand how the wellness dimensions of physical, mental and social overlap and interplay, so any dietary efforts are compromised if the 'whole person' is not taken care of. On a personal note, I also truly care about our state of health as a collective population and think very deeply about how the structure of our society, the way we operate within it and the manner in which we interact with each other influences our quality of life.

Australian data from 2023 indicates that our average daily internet use is trending downwards (5hr and 51min) but social media use is concurrently increasing (2hr 4min). In other words, nearly 1 in 3 minutes of internet use is now ascribable to social media use (2). Two hours plus change is a decent chunk of our waking hours and, when you factor in the type of activity this entails and what our brain is doing whilst it takes place, it's important to consider the implications.

I am certainly not anti-technology on the whole, nor do I believe that anything is all bad. This includes the concept of social media, so I've aimed to address the available evidence through a balanced viewpoint with commentary surrounding net outcome and actual versus potential effects.

'Men seldom moved their bodies; all unrest was concentrated in the soul.'

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, 1909

Technology and wellness

First things first - of COURSE a tool that has the capacity to bring people together in the billions - 4.9 billion in 2023, to be precise (3) - has enormous potential to favourably contribute to public health. Here are some of these opportunities:

Online communities have the potential to support health promotion initiatives by fostering trust and facilitating positive relationships between patients and their healthcare provider, as well as between the public and its health care system (4);

With such wide reach, they have the potential to meaningfully support far-reaching health promotion campaigns, health interventions, medical information dissemination and health research (4);

There is potential to transform platforms from posing a particular wellbeing risk to young people that can worsen mental illness symptoms to facilitating interventions that actually improve health outcomes in this population (5). They could support those experiencing mental illness by facilitating social interaction without additional face-to-face pressures and encouraging sustained engagement in programs (6).

The caveat here is that these benefits rely on very well planned and detailed program structuring to avoid potential ethical, moral, privacy, legal and societal ramifications (4,5,6). They also require the general public to differentiate reliable, evidence-based information from the poor quality, anecdotal variety where conflicts of interest are unclear, and which more typically currently propagates on social media platforms (7).

In sum, realising these benefits would require a dramatic shift in design and utilisation of the platforms from their current form, and in its users themselves.

'Those funny old days, when men went for change of air instead of changing the air in their rooms!'

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, 1909

Social media and public health

Neurochemistry

Okay, let's try to keep this section reasonably simple and absent of too much biochemical jargon. The relationship between social media use and our brain is an emerging research field and the longer term implications of the identified risks have not yet been observed. The long and short of the current understanding is that the structures of social media platforms and, more broadly, the capacity for us to rapidly shift from one compelling stimulus to the next via the internet, are linked to activations in our brain that differ from 'real world' social interactions (5,12).

We'll get into the specific mechanisms used by social media companies to elicit compulsive behaviour later, but their very design triggers our brain's innate reward systems, keeping us wanting more and more (12). Chemically speaking, this occurs in pretty much the same way as when using other addictive substances - by activating our 'feel good' neurotransmitters, particularly dopamine (12). This is why it feels so good yet so compulsive to keep endlessly scrolling, switching windows, clicking hyperlinks and providing 'likes', and why we can lose so much time without even realising (5,9,16). Through these dopaminergic mechanisms, these social media apps elicit, reinforce and perpetuate compulsive 'checking behaviours' by providing 'informational rewards' every time a smartphone is checked, even when checked very frequently, by ensuring there is always fresh content at the top of our feed or a simple thumb scroll away (5).

It's not just the navigational functions that elicit these compulsions. You know those people on social media who can't seem to stop posting about every little thing that happens throughout their day? Are YOU one of these people? Well, here's why. Self-disclosure on social media platforms also activates the brain's reward centre, and this brain activity actually increases from around 30-40% in non-virtual life to a whopping 80% on social media (12)! It's no wonder those people can't stop!

All habits are reinforced through innate rewards, and this perpetuation also occurs in social media use - the more we get, the more we want (12). This, of course, is the premise of addiction. What makes social media platforms particularly addictive is that the rewards derived through their design are immediate, endless and require minimal effort (12).

In addition to functional effects, there is evidence that intensity of social media use is uniquely linked to structural changes in the amygdala - the primary emotion-processing area of the brain - as well as the brain areas involved in addictive behaviour (11). With all that we now know about neuroplasticity at all ages, this type of digitally-induced rewiring warrants consideration.

Cognition and mental performance

The way in which we use social media has more extreme effects on our brain's performance and functioning than you may realise. These platforms encourage us to keep quickly switching our attention from one thing to another. You may think that this 'practice' would increase one's ability to multitask but, on the contrary, research has found that those who heavily partake in media multitasking actually perform worse on task-switching ability tests, likely due to a reduced ability to filter out interference from irrelevant distractions (11).

So this limitless stream of stimuli, notifications, hyperlinks, 'rabbit holes' and prompts negatively effects our ability to pay attention and focus. Unlike 'real world' content engagement (e.g. reading a printed magazine), even engagement in this type of digital environment for a duration as short as 15 minutes can reduce our attentional capacity for a prolonged period of time after going offline (5). Not only can this contribute to poorer academic outcomes and work underperformance, it is also linked to poorer memory function, less empathy, increased impulsivity and higher anxiety (9,11,12,17).

And it's not just young people at risk: lower 'real world' engagement in preference of virtual environments may also accelerate loss of cognitive function in the ageing population (5).

'Above her, beneath her, and around her, the Machine hummed eternally; she did not notice the noise, for she had been born with it in her ears.'

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, 1909

Our brain on social media

By now you may be wondering 'why do some people seem to engage with social media use more than others, and why does this engagement effect everybody so differently?' There are certainly some individual differences at play, as well as an evident bidirectional relationship where mental health is concerned.

The continuing theme centres upon 'excessive', 'chronic', 'problematic, or 'addictive' use of social media. There are currently no universally agreed definitions of these terms. However it is defined, the evidence indicates that higher social media use can have significantly detrimental consequences for emotional wellbeing and mental health, causing negative experiences including:

general unhappiness and dissatisfaction with life (12,18)

poor sleep quality (5,9)

lower general wellbeing (8,9,12,17)

increased risk of mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, stress and distorted body image (8,9,11,12,18,19)

The structure of social media platforms likely contributes to these poorer wellbeing outcomes by hijacking our innate social needs and tendencies in a number of ways. From an evolutionary perspective, our brains have learned that it is imperative for survival that we remain an active part of our tribe. Far more serious than just a cute acronym, social media can facilitate an obsessive level of FOMO ('fear of missing out'), which can be an aspect of social anxiety, via compulsive platform checking (12).

We also tend to make upward social comparisons which, outside an unaltered real life setting, can cause us to have unrealistic expectations of ourselves and result in poor self-appraisal (5,9,12). And what better format to do so en masse and feel bad about ourselves than the artificial, endless social media feed which, as Firth et al. (2019) describes, "...showcases hyper-successful individuals constantly putting their best foot forward, and even using digital manipulation of images to inflate physical attractiveness" (5)?

In fact, there may be a correlation between our patterns of use and the impact of that use on wellbeing (11). For example, more passive engagement, and that which promotes unrealistic self-comparison and jealousy (e.g. solely browsing and scrolling), has been more consistently linked with poorer outcomes than more active engagement (e.g. engaging with others and self-disclosing) (8).

Another explanation for these observations can be found in The Displaced Behavior Theory model, which postulates that the more time spent on sedentary activities such as social media the less time there is for in-person social interactions, which have been shown to protect against mental health issues (5,11,19). So it's a double whammy: more damaging input PLUS less protective input.

'“I don’t think this is interesting you. The rest will interest you even less. There are no ideas in it, and I wish that I had not troubled you to come. We are too different, mother.”'

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, 1909

Social media and mental health

Use of social media in itself is not necessarily harmful, but what about when it reaches the point of what we could term an addiction? The mechanisms used by social media companies make it addictive both physically and psychologically (12). Whilst there is not yet a universally agreed definition for this term (20), one example that incorporates the generally accepted elements is that social media addiction is:

"...a behavioral addiction that is defined by being overly concerned about social media, driven by an uncontrollable urge to log on to or use social media, and devoting so much time and effort to social media that it impairs other important life areas." (12)

The symptoms of social media addiction mirror those we see in other forms of addiction, including (12,20):

changes in mood derived through social media use

an obvious or noticeable preoccupation with social media

continuously increasing tolerance and use over time

negative withdrawal symptoms as a result of the restriction or cessation of use

interpersonal conflict or problems arising as a result of use

relapse following a period of abstinence

Like all addictions, some people are more vulnerable and susceptible than others depending on personality (9,17), age (11,18) and life circumstances leading to using social media to cope with undesirable emotions or mental health issues, or as a substitution for otherwise unmet interpersonal needs (9,12). This overuse only perpetuates these issues, leading to 'real life' implications that reduce quality of life and the ability to cope in the real world, which continues to increase use in a vicious cycle of reinforced dependency (12). What we are really talking about here is an industry that is taking advantage of those most vulnerable to its product.

This type of behavioural addiction can reduce quality of life in several ways, including:

elevated loneliness (8,18,21)

increased risk of psychological and wellbeing disorders (8,9,11,12,18,19,21)

loss of positive emotions (21)

reduced social communications (21)

lower academic achievement (9,11,12)

work and employment issues (9,17)

'But Humanity, in its desire for comfort, had over-reached itself.'

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, 1909

Healthy use vs. addiction

By now, the theme is pretty clear, right? Higher, more intense use of social media increases the risk of negative wellbeing experiences and outcomes. In contrast, a moderate, functional use is unlikely to pose dramatic detriment to our quality of life, and can even offer some benefits.

Well yes...but here's the rub. They're not playing a fair game.

Let's think back to what is happening in our brain during social media use - dopamine, reward centre activation, structural brain changes and all that.

The truth is, the design of these platforms contains mechanisms specifically aimed at eliciting addictive, compulsive use. Make no mistake, they know what they're doing - these companies have researched, studied and tested their features to make them as compelling to users as possible (5).

What are these mechanisms, you might ask? As you read the following list, you may begin to think about how you experience these functionalities yourself. Here are six design mechanisms that social media companies use to attract and keep our attention:

1) Endless scrolling and refreshing opportunities

They provide an increasingly immersive 'flow' of content, eliciting time distortion (17). This flow is, by nature, unending, never reaching a natural cessation or sense of resolution that would typically mark a point at which to quit the activity - our brain knows there is always MORE reward to be had, and it can't stop wanting it!

2) Gentle (but constant) behavioural nudges

These create social pressure on users to be perpetually available and communicate without delay, e.g. read receipts (17). The earlier reference to FOMO also ties in here.

3) Constant monitoring of online activity

By doing so, social media platforms use algorithms to determine the content that will be most appealing to you in order to engage you as powerfully as possible (17). You know the saying "You gotta give the people what they want!" Many people don't realise that it's not just active activity that is logged and used, but also passive engagement such as how long you hover over something in your newsfeed (17).

4) Constant stream (or dearth) of social feedback

This is done through likes, comments, follows, etc. and targets our innate social need for validation and acceptance (17). These social reward and comparison processes are powerful, and these companies know that we can't get enough of it.

5) The 'attraction mechanism'

This strategy ensures that the content that gains the most tracked digital attention on aggregate and is therefore, theoretically, the most universally engaging and appealing drowns out less attractive content and is pushed to the forefront (5).

6) Uninterrupted access

The above mechanisms operate effectively in conjunction with, and facilitated by, ubiquity of access via smartphones (5, 17), which nowadays tend to be in constant possession of their owner.

So it's a little more complex than simply advising 'just don't use it'.

In light of these very deliberate design decisions, it's clear that addiction, or at least compulsive use, is not only a possible risk but in some ways the ultimate goal. Through this lens, we can consider that, unlike other addictive substances or behaviours:

social media use is widely socially endorsed, accepted and even encouraged;

it is easily accessible, with smartphone use in Australia estimated as being around 86% (22), including to children - most users now get their first smartphone somewhere between the ages 7.5 and 12 (23) (there are obviously far higher age limits for other legal high-risk substances and behaviours such as cigarettes, gambling and alcohol);

the long-term ramifications are not yet known, and research is in its infancy - so the actual risks and effects are as yet unknown. As a result, people may dismiss concerns as unfounded or mere overreactions.

'“Some one is meddling with the Machine—” they began. “Some one is trying to make himself king, to reintroduce the personal element.”'

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, 1909

So...as long as I use it moderately...?

When Socrates said "The unexamined life is not worth living", he highlighted the importance of travelling through life with conscious thought and considered activity. I think about this often in my own life - not just doing things because 'that's what we all do', but actually considering the value of each option to me, personally. This is why I invested so much time and effort into writing this - to support others to make more informed decisions that affect their health and quality of life. I see this as my primary job as a wellness practitioner.

Free will and individual decisions are of course vital for wellbeing and I am certainly not here to tell anyone what to do, or judge them for how they do it! I am not advocating for a complete exodus from social media, but I do want to beat the drum of personal responsibility to ourselves in being aware of the systems at play around us and how they influence our behaviour and, ultimately, our health outcomes.

Through this type of knowledge we can make choices with our eyes wide open. A little more thoughtfully. A little more considered. A little more examined.

Perhaps enjoying a few more moments each day unplugged from the Machine.

'"...That is why I want you to come. Pay me a visit, so that we can meet face to face, and talk about the hopes that are in my mind.”'

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, 1909

Final thoughts

Has this inspired you to prioritise more real life interaction?

Are you a local business owner who has a positive effect on the quality of life of your clients, customers or community? Do you know of one whom you would like to nominate? Or are you just interested in more content like this, and receiving monthly stories that promote real life wellness?

Sources

1 Denniss, E., Lindberg, R. and McNaughton, S.A. (2022). Development of Principles for Health-Related Information on Social Media: Delphi Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(9), p.e37337. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/37337

2 WE ARE SOCIAL (2023). Digital 2023 Australia: 1 in 3 Australians use social networks for brand research. [online] We Are Social Australia. Available at: https://wearesocial.com/au/blog/2023/02/digital-2023-australia-1-in-3-australians-use-social-networks-for-brand-research/

3 Shewale, R. (2023). Social Media Users — How Many People Use Social Media In 2022. [online] Demand Sage. Available at: https://www.demandsage.com/social-media-users/

4 Kanchan, S. and Gaidhane, A. (2023). Social Media Role and Its Impact on Public Health: a Narrative Review. Cureus, [online] 15(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.33737

5 Firth, J. (2019). The ‘online brain’: how the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry, [online] 18(2), pp.119–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20617

6 Naslund, J.A., Bondre, A., Torous, J. and Aschbrenner, K.A. (2020). Social Media and Mental Health: Benefits, Risks, and Opportunities for Research and Practice. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, [online] 5(3), pp.245–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00134-x

7 Ventola, C.L. (2014). Social Media and Health Care Professionals: Benefits, Risks, and Best Practices. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, [online] 39(7), pp.491–520. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4103576/

8 Keum, B.T., Wang, Y.-W., Callaway, J., Abebe, I., Cruz, T. and O’Connor, S. (2022). Benefits and harms of social media use: A latent profile analysis of emerging adults. Current Psychology, [online] 42(27). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03473-5

9 Rajesh, T. and Rangaiah, B. (2022). Relationship between personality traits and facebook addiction: A meta-analysis. Heliyon, 8(8), p.e10315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10315

10 Pollmann, M.M.H., Norman, T.J. and Crockett, E.E. (2021). A daily-diary study on the effects of face-to-face communication, texting, and their interplay on understanding and relationship satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 3, p.100088. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100088

11 Korte, M. (2020). The impact of the digital revolution on human brain and behavior: where do we stand? Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, [online] 22(2), pp.101–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.2/mkorte

12 Hilliard, J. (2023). Social media addiction. [online] Addiction Center. Available at: https://www.addictioncenter.com/drugs/social-media-addiction/

13 Nguyen, M.H., Gruber, J., Marler, W., Hunsaker, A., Fuchs, J. and Hargittai, E. (2021). Staying connected while physically apart: digital communication when face-to-face interactions are limited. New Media & Society, 24(9), p.146144482098544. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820985442

14 Sherman, L.E., Michikyan, M. and Greenfield, P.M. (2013). The effects of text, audio, video, and in-person communication on bonding between friends. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, [online] 7(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.5817/cp2013-2-3

15 Seltzer, L.J., Prososki, A.R., Ziegler, T.E. and Pollak, S.D. (2012). Instant messages vs. speech: hormones and why we still need to hear each other. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(1), pp.42–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2011.05.004

16 Sherman, L.E., Hernandez, L.M., Greenfield, P.M. and Dapretto, M. (2018). What the brain ‘Likes’: neural correlates of providing feedback on social media. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, [online] 13(7), pp.699–707. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsy051

17 Montag, C., Lachmann, B., Herrlich, M. and Zweig, K. (2019). Addictive Features of Social media/messenger Platforms and Freemium Games against the Background of Psychological and Economic Theories. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, [online] 16(14), p.2612. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142612

18 Sergey Yu Tereshchenko (2023). Neurobiological risk factors for problematic social media use as a specific form of Internet addiction: A narrative review. World Journal of Psychiatry, 13(5), pp.160–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v13.i5.160

19 Karim, F., Oyewande, A. and Abdalla, L. (2020). Social Media Use and Its Connection to Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Cureus, [online] 12(6). doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8627

20 Tullett-Prado, D., Doley, J.R., Zarate, D., Gomez, R. and Stavropoulos, V. (2023). Conceptualising social media addiction: a longitudinal network analysis of social media addiction symptoms and their relationships with psychological distress in a community sample of adults. BMC Psychiatry, [online] 23(1), p.NA–NA. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04985-5

21 Chegeni, M., Shahrbabaki, P.M., Shahrbabaki, M.E., Nakhaee, N. and Haghdoost, A. (2021). Why people are becoming addicted to social media: A qualitative study. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, [online] 10(1), p.175. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_1109_20

22 Hughes, C. (2023). Australia - smartphone penetration 2012-2022. [online] Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/321477/smartphone-user-penetration-in-australia/

23 Fitzgibbins, M. (2023). Young People And Mobile Phones. [online] Road Sense Australia. Available at: https://roadsense.org.au/young-people-and-mobile-phones/

© Sharon Jenner 2023

Location & Contact

Essendon, VIC & Online

Email: hello@intrinsicnutrition.com.au

Phone: 0412 905 582

Subscribe for exclusive content

No spam, I promise!

Just quality content for intrinsic learning and motivation once in a while.

We’ve all heard the utterance ‘I’d get off social media but it’s the best way for me to keep updated on what is happening in the lives of everyone I know’.

Unsurprisingly, teenagers and young adults in particular commonly report feeling better connection with friends, interaction with more diverse groups of people and a sense of social support when using social media (8). Indeed, we are all drawn to these platforms due to similar motivations as those that compel us to form social bonds in the non-digital world: to form friendships, gain social support and exchange ideas and information (5, 8). Healthy use can support the maintenance of real-world relationships, act as a source of entertainment and satisfy needs for popularity, self-affirmation and social approval (9).

So what's the problem, then? Well, before you warm up that thumb for another scrolling session, WAIT! Let's look at some of the negative consequences of heavy reliance on text-based social media communication in favour of face-to-face interaction. This reliance can actually compromise our real-world relationships in several ways, including:

Less reported warmth and affection amongst friends (10,14)

Lower sense of liking and bonding with others (10,14)

Reduced romantic relationship satisfaction (10)

Lower sense of understanding between romantic partners (10)

Increased social comparison and self-negativity (8)

Increased sense of isolation (8,12)

Difficulties dealing with solitude (11)

A lack of social skills (11)

Interestingly, other forms of remote communication such as voice and video calls ('higher social presence media') do not yield the same level of social connectedness issues (13,14,15). So it's not the lack of in-person contact that is the problem - there is something uniquely problematic about text-base forms of communication.

These contradictions may indicate some form of ‘sweet spot’ in terms of degree and nature of use, in that digital communication on social media can help to maintain relationships and create a sense of togetherness only when used moderately and when healthfully intertwined with adequate face-to-face communication (13).

There may be a few functional reasons for these observations. Regardless of the hundreds – or even thousands – of social media connections a person may have, our social cognition capacities seem to remain as constrained online as they are offline, for example the ability to engagingly connect with a maximum of only three people at a time (5). In true 'less is more' fashion, the sensation of being constantly connected with hundreds or thousands of people can actually cognitively overburden our brain and lead to lower wellbeing outcomes (11).

Unlike in organic, real-world social activity, social media platforms also place a quantitative figure on our social success (or failure) through black and white metrics such as number of connections (e.g. ‘friends’), validation (e.g. ‘likes’) and support (e.g. ‘followers’). This type of in-your-face measurement of acceptance or rejection increases compulsive use by tapping into our innate desire for immediate, self-defining feedback (5). Unsurprisingly, where we are not satisfied with this quantifiable digital social performance, our wellbeing can suffer (5).

'...she fancied that he looked sad. She could not be sure, for the Machine did not transmit nuances of expression. It only gave a general idea of people — an idea that was good enough for all practical purposes, Vashti thought.'

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, 1909

Social connectedness